Introduction

At Zomato, we manage more than half a billion images, which are integral to various aspects of our platform. Every day, we process close to 100,000 new images, contributing to petabytes of data, with a daily influx of approximately 500 GB of fresh visual content.

In this blog, we delve into how we built a neural network-based machine learning model to classify these images into categories like food, ambiance, menu, and more. This post is particularly valuable for professionals at startups deploying their first machine learning use case, students eager to learn how to turn innovative ideas into practical solutions, and anyone interested in the technical nuances of scaling deep learning models in a production environment.

What You’ll Learn

This post is driven by our journey of taking a deep learning model from concept to production, addressing the unique challenges of operating at Zomato’s scale. Whether you’re a data scientist, an engineer refining your deployment strategies, a tech enthusiast, or a professional exploring the practical applications of AI, the insights shared here are relevant across various stages of a machine learning project.

By the end of this blog, you will have gained:

- Comprehensive Understanding of Image Classification: Explore how we systematically approached the categorization of vast amounts of visual data into meaningful categories using neural networks.

- Valuable Practical Insights on Deployment: Understand the challenges we faced when deploying our first deep learning model at scale, and learn how we successfully navigated these obstacles.

- Key Lessons from Real-World Implementation: Discover practical lessons from our experience deploying this model in production, including reflections on what we would do differently if we were to undertake this project today.

Whether you’re just starting out, looking to refine your machine learning deployment process, or simply interested in the application of deep learning at scale, this blog post offers actionable insights to help you navigate the complexities of building and deploying AI models effectively.

The Need for Image Classification

As a restaurant search, discovery, and delivery platform, Zomato’s primary sources of images are:

- User-Uploaded Images: These are images uploaded by users when they visit or order from a restaurant and write reviews.

- Team-Collected Images: These are images our team gathers from restaurants while listing them on the platform.

Image classification serves several critical functions at Zomato:

- Enhanced User Experience: By categorizing images into collections such as food and ambiance, we can help users quickly find ambiance images. Previously, we manually tagged around 10-20 images per restaurant as food or ambiance shots. To enhance the user experience, we aimed to categorize all images uploaded across the platform.

- Content Balance: The majority of images uploaded to Zomato are food-related, which can overshadow ambiance images. Classifying images allows us to surface ambiance shots more effectively, improving the visual balance of restaurant pages.

- Content Quality Assurance: The quality of content on our platform is paramount. We have a dedicated team of moderators who work tirelessly to ensure that only the best content is showcased to our users. Automated tagging, such as identifying human faces or selfies, can significantly improve our photo moderation turnaround time.

- Menu Management: Similarly, if an image appears to be a menu, we want our content team to review it to ensure only the highest quality menu images—those manually verified by our data collection team are shown to users.

Building the Classifier

Image classification is fairly straightforward from a technical standpoint, especially when working in a Jupyter notebook. However, our challenge was magnified by the fact that this was our first deep learning project to be deployed in production, and the scale was daunting. We needed to build a system capable of moderating nearly half a million images daily. The initial model was trained in 2016, and this blog post not only recounts our experience from that time but also provides insights into how we would approach retraining today.

To streamline the entire process—from data gathering to preprocessing, model training, and validation—we utilized Luigi. Luigi allowed us to create a DAG-based pipeline, ensuring that each step was dependent on the completion of the previous ones. This approach was crucial for maintaining the integrity and flow of the pipeline. Luigi also provided a user-friendly visual interface, which made it easier to monitor the progress of our data and model pipeline.

Dataset Gathering

Before we could demonstrate the effectiveness of this “new deep learning” approach to our PMs, we needed a substantial amount of labeled data. We started with four primary labels: food, ambiance, menu, and human. In the future, we planned to expand these categories to include indoor shots, outdoor shots, drinks, and dishes.

Food & Ambiance

At Zomato, we had manually tagged images classified as food and ambiance shots. We downloaded 50,000 images for each category to build our classification dataset.

Menu

Generating the dataset for menus was the most straightforward task. Given Zomato’s vast collection of manually tagged and categorized menus (one of the foundational elements of the company), we downloaded 50,000 menu images from S3, distributed across randomly selected restaurants.

Humans

Curating the dataset for humans was more challenging. We initially used the YouTube dataset, which includes images with mixed scenes. For example, some images contain humans, but they might also exhibit characteristics of an ambiance shot, leading to potential misclassifications. Our strategy was to train a basic model with this dataset, generate approximate labels, and have our internal moderation team quickly correct them—significantly speeding up the labeling process compared to starting from scratch.

To address the need for face shots, which were limited in the YouTube dataset, we incorporated the LFW dataset by UMass, also known as the Labeled Faces in the Wild dataset.

Dataset Preprocessing

After gathering the data, our next step was preprocessing. We had a large collection of images categorized into food, ambiance, menu, and human. For model training, it was essential to iterate over this data efficiently and feed it into Keras.

To handle this, we used the Hierarchical Data Format (HDF5) to create an out-of-memory iterable dataframe. With the pythonic interface provided by h5py, we could slice and manipulate terabytes of data as if they were numpy arrays in memory.

We resized each image to 227x227 pixels and performed several cleaning steps. Additionally, we augmented the dataset by creating multiple variations of each image through rotation, scaling, zooming, and cropping. In future retraining efforts, we plan to explore using the RecordIO format for storing images in classification tasks.

Training the Model

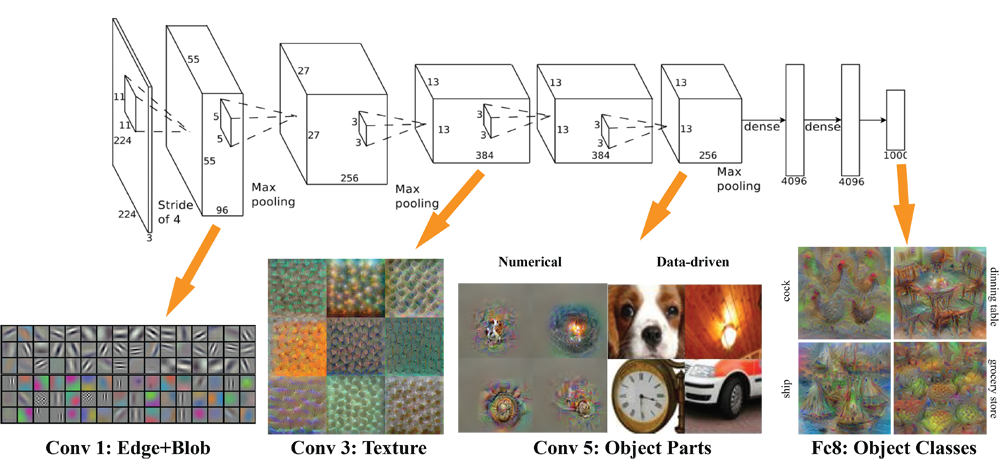

We began our journey with AlexNet, a well-established model in 2016 with multiple open source implementations available. Alongside AlexNet, we experimented with other architectures like Inception v3 and Google LeNet. While these models served us well at the time, today there are more accurate and efficient options available, such as ResNet, MobileNet, and others.

We chose Keras as our framework due to its flexibility, particularly its ability to switch backend engines (e.g., Theano, TensorFlow) in the future. In 2016, installing TensorFlow wasn’t as straightforward as it is today (pip install tensorflow), so we opted for Theano as our backend engine. Theano provided reliable and consistent results and was easier to set up with Keras during that period. Although Keras remains our preferred choice for writing models, if we were to do this now, we would leverage a platform like AWS Sagemaker for training.

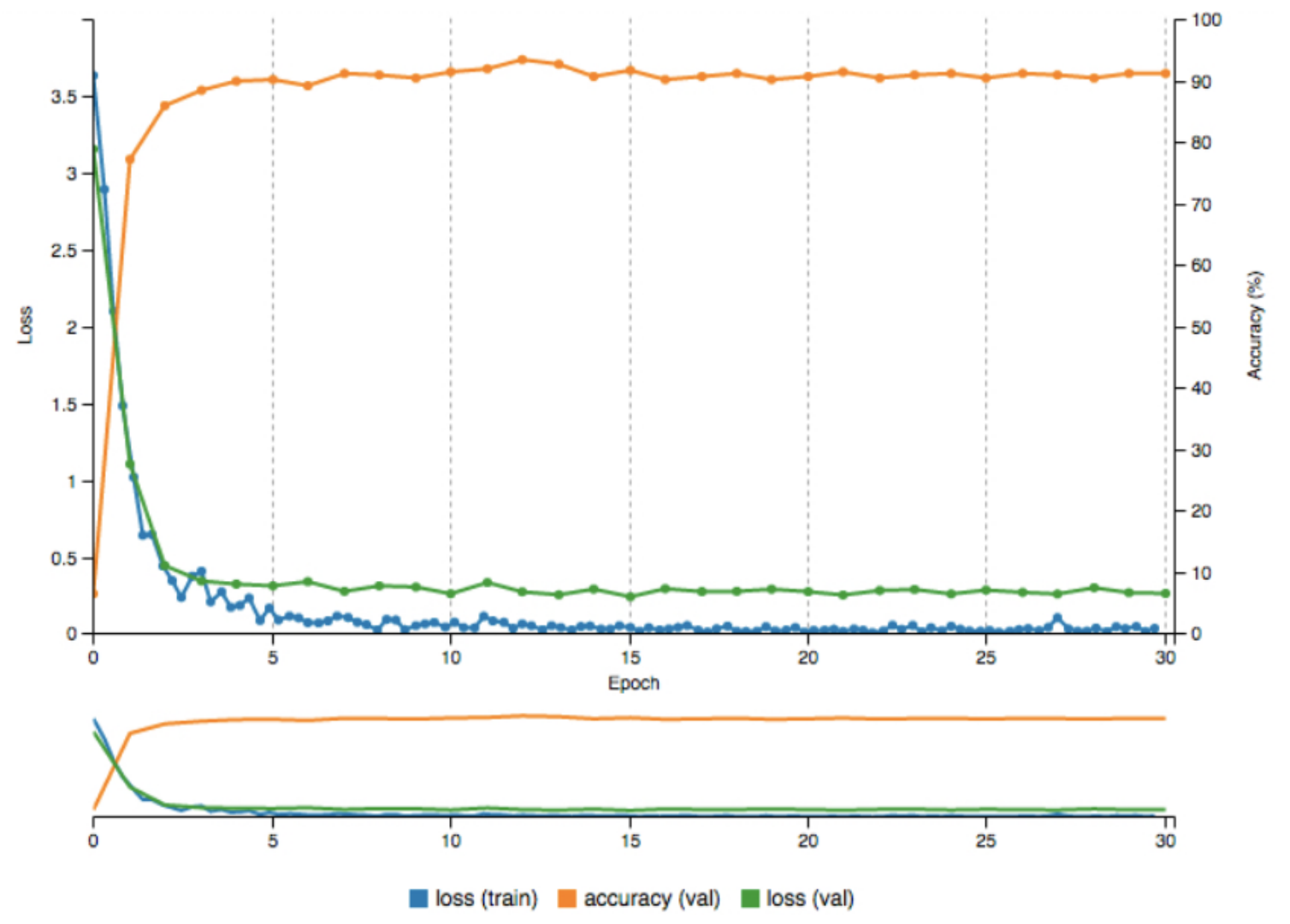

We initially trained our models on in-house GPU servers before transitioning to AWS GPU p2.xlarge instances to scale our efforts. Rather than using transfer learning on an existing ImageNet model, we trained our models from scratch to better fit the unique characteristics of our restaurant industry domain photos. We worked with 50,000 images for each of our four classes: food, ambiance, menu, and human. As illustrated in the graph below, our efforts resulted in achieving approximately 92% validation accuracy.

Production Deployment

For serving the model, we developed an internal API using Flask. We enhanced it with authentication layers and deployed it within our internal VPC network. While today, tools like ONNX and TensorFlow Serving are commonly used for model inference, back in 2016, the landscape for ML model inference was still maturing. As a result, we chose to proceed with a Flask-based API.

We containerized the API using Docker, with a Miniconda3 base image. After every code merge, Jenkins would run unit tests and build the final Docker image, which included both the application code and the latest version of the model. Automated tests were then executed on this image to validate the inference accuracy on a predefined set of images. Once these tests passed, the Docker image was deployed to AWS Elastic Beanstalk, where the API could automatically scale based on incoming request load.

Once the API was live, every time an image was uploaded to Zomato, it was queued for processing. Multiple workers would pick the image from the queue, request inference scores from the API, and save these scores in our database.

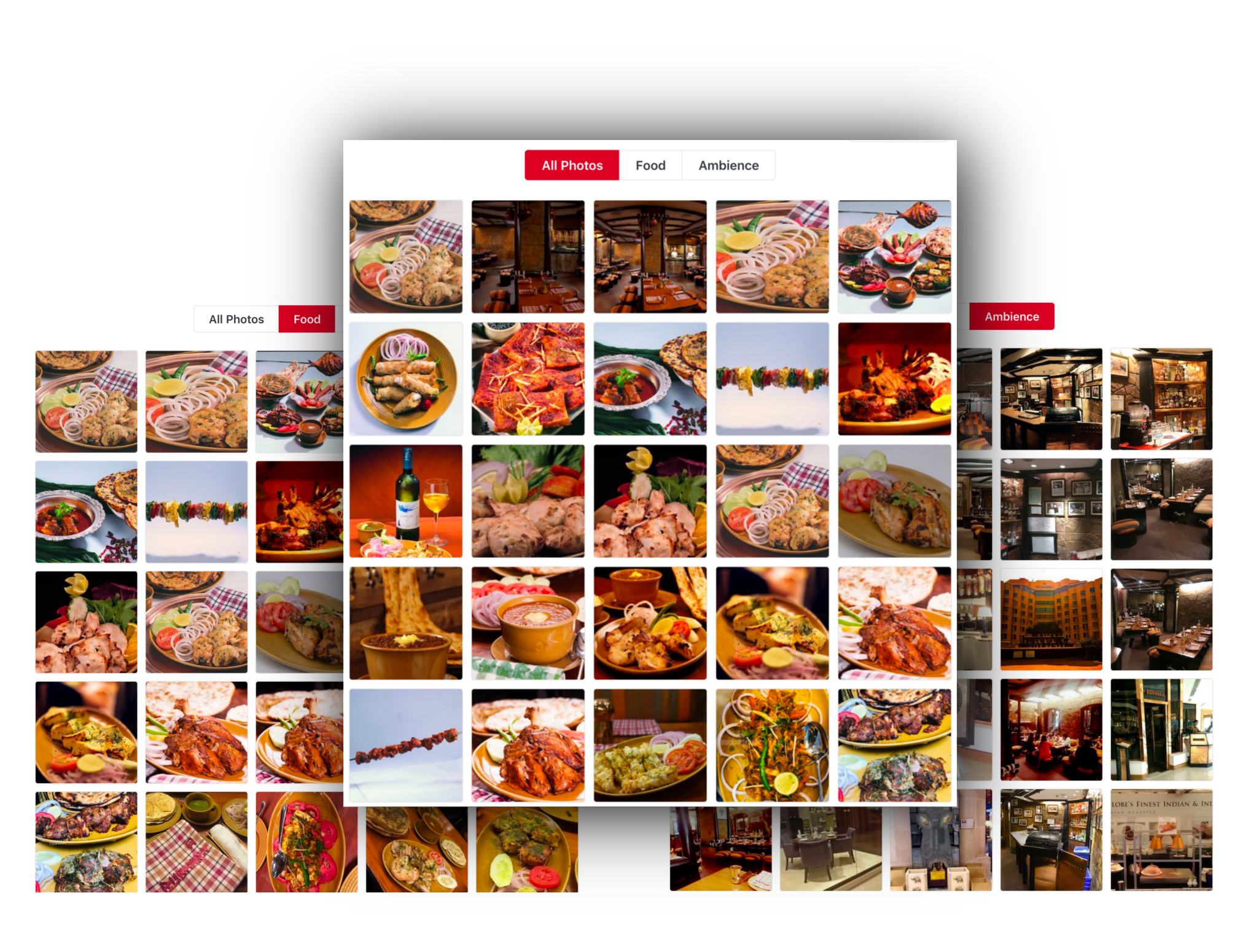

Initially, we utilized this setup on the backend for moderation and various other internal use cases. On the product side, we made this live for Food & Ambiance classification. It was first integrated into our web platform, with upcoming releases soon adding it to our mobile apps. The image below illustrates the impact of using image classification, showing the results before and after its implementation.

This example highlights how image classification can make it easier to find ambiance shots, especially when the initial images on the restaurant page are predominantly food shots.

Evolution

From our first model, we learned to streamline our data gathering and model training processes significantly to reduce the TAT from an idea to the model generation, reducing time-to-deployment. Future blog posts will cover our evolving ML training processes and other models in production. Stay tuned for updates.

We are rapidly expanding our machine learning team and have grown in number by 5x in just last year. Check out our careers page if you’re interested in joining us.