This is one of the very first project picked by me during my first few months at Zomato. This is a cross post from Zomato Engineering Blog

Given the large number of features we have in our apps, performance is of prime importance, and it’s something we look at very closely. We’re constantly tinkering with various components of the app to improve speed, reduce the memory footprint, and optimise battery usage. We’ve often found that networking proves to be a big bottleneck when it comes to the speed of our app. Efficient networking can not only speed up the app, but also save considerable network bandwidth.

Recently, we got down to identifying areas of improvement in the network operations being performed throughout our Android app. We can split a network operation in the three broad parts –

- Opening a connection using an HTTP client. Our apps used Apache as the HTTP client.

- Fetching API responses on background threads. Our apps used the standard AsyncTask class for fetching API responses.

- Parsing responses into Java objects. Our apps used the VTD-XML parser for parsing XML data in API.

As soon as we picked up this project, we knew that there was a lot of work that had been pushed too long. We considered each of these components one by one, looked at the specifics, analysed all the alternatives available and dug deep to understand what we could optimise and improve. Let’s look at each one of these three aspects in detail.

Aspect #1. Making a Network Connection

With Apache being deprecated starting with Android 6.0, we had to go with a new HTTP client. We picked the familiar OkHttp as the HTTP client for our Android apps. Now, making such a big change isn’t straightforward, and involves reworking large parts of the codebase. However, our code was structured in a way that abstracted the underlying HTTP client from the rest of the codebase, which made it easy for us to change the HTTP client without moving much — a practice we follow to be future-safe.

Earlier, with Apache, we had implemented GZIP compression for all the HTTP requests and responses on our own. OkHttp does this by default, so changing the HTTP client from Apache to OkHttp reduced our average response time by 30%, which is a huge improvement. Keeping up with the times, we enabled HTTP/2.0 on our web servers, and this was a further advantage as OkHttp also enabled socket sharing for all connections to the same host.

This change was substantiated soon after, when OkHttp became the engine that powers the default Android HTTP client HttpUrlConnection as of Android 4.4.

You can see a detailed comparison of HTTP/1.1 vs HTTP/2.0 in this demo , where it loads a 180-tile grid image in separate calls (pro tip: to actually see the magic happen, open the network section in your browser’s developer tools while you watch the demo).

Aspect #2. Performing Network Operations

For fetching data from our API, all the network calls must always run on background threads (duh!). Using the good old AsyncTask object for every API call seemed to be the right way of doing this. However, with time, we have found that we did not have the ability to cancel network calls once initiated; the need to cancel network calls stems from trying to save network bandwidth and improve UX. Furthermore, we had run into the serial nature of execution of AsyncTasks many times, and we seriously considered looking beyond AsyncTask at this point.

While we were at it, we wanted an abstracted asynchronous layer, because all the AsyncTasks were heavily interfaced with the application logic and the UI (never on the same thread though, obviously). We considered the popular Android Async clients — Retrofit, Volley, and the like. These offered greater speed, truly concurrent background threads, and even the abstractions we were looking for. The Square-powered Retrofit seemed to fit our use case better, and most of the Android forums & blogs consider it the fastest Android Async client out there.

Again, we stared at the mammoth task of changing almost all the files in our complex app, and it involved a lot of code just to test. This was not as easy as the HTTP client change above, because these Asyncs were all over the code. Not only was this a big task, but also required us to be extremely careful. However, the upside of moving over to Retrofit far outweighed the massive one-time effort we had to put in to remove all AsyncTasks.

Aspect #3. Parsing Data

A considerable part of our development time was being spent on writing the custom parsers for our various objects, which is a rather laborious and time-consuming effort. Moreover, our parser files were huge — close to a staggering 30,000 lines of static code. The possibility of a reduced memory footprint, and trimming down the app size was motivation enough to revamp this archaic parser strategy.

To come up with a simpler and quicker parsing strategy, we considered various techniques. The areas of improvement included the speed of parsing, effort during development phase, the number of lines of code, and readability of code.

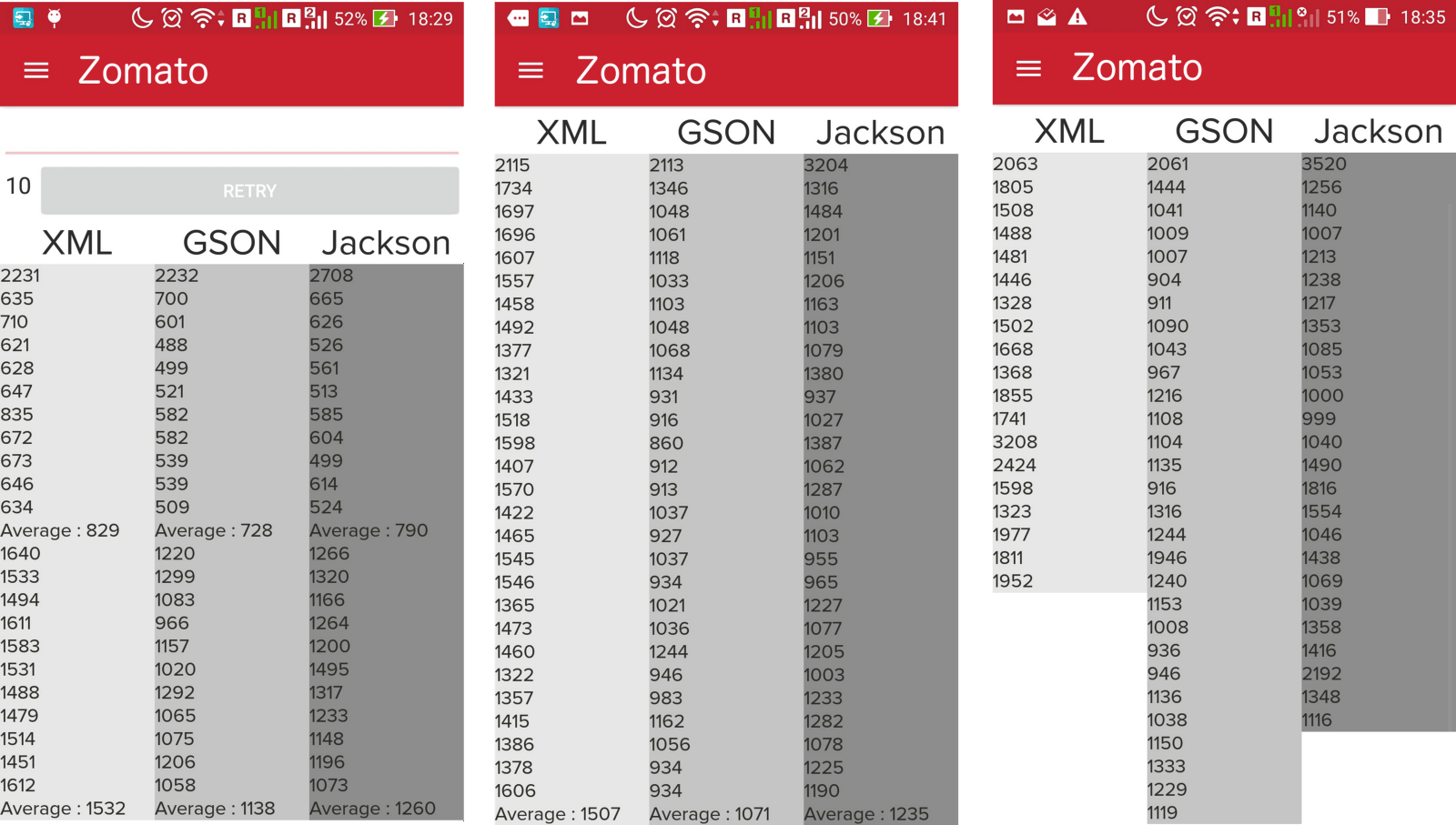

We considered a few approaches, and it came down to three contenders in a showdown — XML, GSON, and Jackson. To validate each of these, we used one of our heaviest API calls — parsing the menus of one of the largest restaurant chains on Zomato, with each of the three approaches. We built a custom app to hit this api multiple times to test our options in real life scenario.

The screenshots above show the results from the custom showdown app. Each row shows the time it took to parse the API response (in ms).

- The first column represents the XML data being parsed with the vtd-xml parser

- The second column results are from parsing with GSON v2.5

- The third column are results from parsing with Jackson v2.7.1

GSON emerged as the winner, but then again, the transition to GSON wasn’t going to be easy. We had to rewrite some parts of our backend API and Android code in a GSON-ready format.

Final Network Stack

After this exercise, our network layer now looks like this:

- OkHttp as our HTTP client, HTTP/2.0 as our protocol

- Retrofit to perform API calls

- GSON to parse API responses into Java objects

We’ve already implemented this in our Zomato for Business app, and we’re currently in the process of making this change in all our other apps on the Android platform, to help improve performance across the board.

We’d like to extend our thanks to all the open source projects mentioned in the post, and to the power of collaborative open source programming.